by Elizabeth Rogers Kotlowski

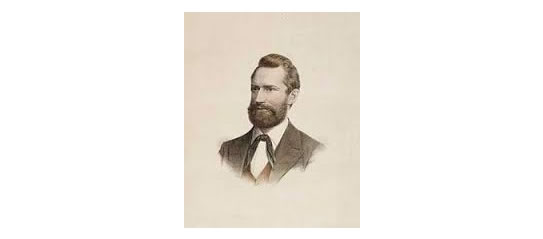

Death seemed imminent. Charles Sturt (1795–1869) and his men were stranded on a sandbar at the Murray–Darling River junction. Confronting them on the riverbank were nearly 600 Indigenous people, painted, armed and making menacing gestures as they sang a war song. This was Sturt’s second exploratory journey into the outback. Would it be his last?

He tried without success to calm the alarmed people on the riverbank. As they drew nearer, they were even more threatening, raising their spears, poised to hurl them. Seeing that it would be impossible to avoid an aggressive conflict, Sturt reluctantly picked up his double-barrelled shotgun and aimed, hoping that firing a shot would scare them off. He pointed his gun at the closest person with his finger on the trigger.

At that very moment, a new group of Indigenous people appeared on the other bank. Sturt recognised one of the new arrivals as someone he’d met and had friendly interactions with earlier, further up the river. This man leapt to the stranded explorers’ rescue. Sturt’s journal records the ‘miraculous intervention of Providence [that is, God’s provision] in our favour’. This saved their lives – and the lives of those who may have been shot.

This was a remote, inhospitable and uncharted part of Australia at the time, but Sturt and his men were out to solve a mystery. If all the major rivers flowed westward, where did they go? Was there an inland sea? By tracing several of these west-flowing rivers, Sturt and his men discovered that they merged into the Murray River and then flowed into the sea in the Great Australia Bight. The mystery was solved; there was no inland sea.

Sturt’s third exploratory journey was one of the most famous central Australian expeditions, the most difficult and dangerous of all his expeditions.

On 10 August 1844, Sturt set out, well-equipped (he thought), from Adelaide with fifteen men, six horse-drawn wagons, a boat and two hundred sheep. They headed north-west from Menindee on the Darling River. They travelled over 4800 kilometres into unknown territory and reached the Simpson Desert. But when the heat reached 53 degrees Celsius and caused the thermometer to burst, they were forced to turn back.

In May 1846, Sturt was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society for his achievements. He documented his great discoveries and numerous scientific observations in his journals. He wrote about his faith and how he took all his plans, difficulties and sorrows to God in prayer, always recognising the ‘Providential care and intervention of God’. He was known for his ability to inspire and maintain the loyalty of his men, even under the most difficult conditions, and for how he usually tried to establish good relationships with the Indigenous people he met.

Sturt was concerned that people might think he went on these journeys purely for the love of adventure, but he really had a genuine desire to help his society through his discoveries. He wrote in his journal that he had ‘an earnest desire to promote the public good, and certainly without hope of any reward than the credit due to a successful enterprise’.

Historian Jill Waterhouse wrote: ‘Sturt, like most Australian explorers faced with a hostile environment, leaned hourly on God’s mercy.’ He slept with a Bible from his father-in-law under his pillow, and once when he had to throw away most of his possessions in the desert, he decided to keep the Bible in preference to an oil lamp.

Sturt had learned some important things about living a Christian life – to trust in God, and to look for ways to benefit society. His Christian faith and character contributed much to the establishing of our nation and he was a great role model.

Further reading:

Elizabeth Rogers Kotlowski, Stories of Australia’s Christian Heritage, Strand, 2006