Think about a newborn baby. When we look at tiny babies, we are immediately struck by their complete and utter helplessness. They depend entirely on adults to give them what they need. And not just babies: children, too, are some of the most vulnerable of all human beings and are totally dependent on the adults around them for their physical, emotional and spiritual wellbeing.

Sadly, not all children have been cared for in this way. And that’s why historical figures like Lord Shaftesbury have needed, at times, to step in and protect children in need.

In 1838, there was a terrible accident at the Huskar Colliery (coal mine) in Britain in which, tragically, 26 children died: 15 boys from 7 to 16 years of age, and 11 girls from 8 to 17 years of age. Partly due to this shocking event, the public became increasingly concerned about the use of child labour in coal mines.

Queen Victoria, the British Queen at the time, took a personal interest in the disaster, and other powerful people also called for change.

Until the mid-nineteenth century, it was accepted in Britain that children as young as five years old could be part of the industrial workforce. Change was needed. Between 1840 and 1842, government inspectors visited the Welsh coalfields and spoke to many child miners. These interviews were presented to Parliament as part of The Commission of Enquiry into the State of Children in Employment. This Enquiry revealed the horrific conditions that children worked in.

Lord Shaftesbury, a British Member of Parliament, had been campaigning since 1828 for something to be done about the terrible conditions and injustices that many people were forced to live under at this time. One of his main concerns was to introduce laws that prohibited the employment of women and children in coal mines. He also wanted the government to provide care for people with mental illness, establish a maximum ten-hour work day for factory workers, and outlaw employing young boys as chimney sweeps.

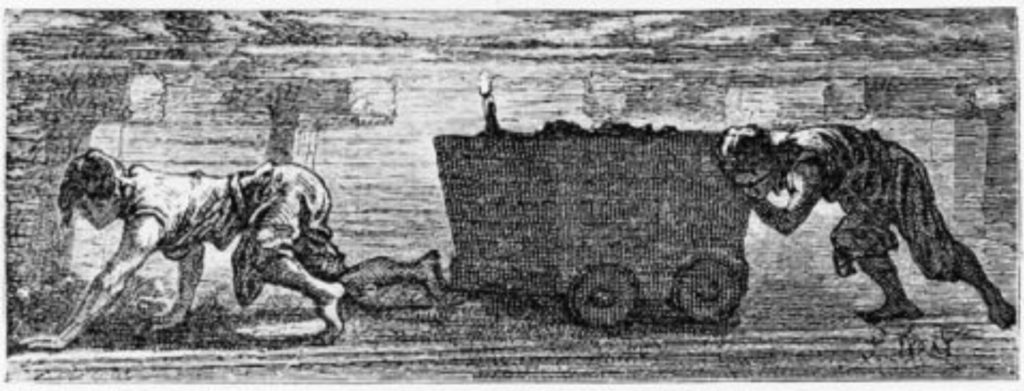

Coal mines in this period were cramped, poorly ventilated and highly dangerous. There was little attention paid to health and safety. Children were often injured or killed by explosions, by mine roofs falling in, or by being run over by carts.

But what were such little children doing working in mines in the first place?

Children performed a number of important tasks underground. They could be door keepers, who operated the ventilation doors to let coal carts through; drammers, who pulled coal carts to and from the coal face; colliers’ helpers, who assisted with the actual coal cutting, usually alongside their fathers or older brothers; or drivers, who led the horses that pulled wagons full of coal along the main roadways underground.

Philip Philips, aged 10, from Brace Colliery in Llanelli, was accustomed to the dangers of ladders:

‘I help my brother to cart. I can go down the ladders by myself. I am not afraid to go down the pit.’

The Government Inspector who interviewed Philip during the Enquiry climbed down these ladders himself – but with difficulty. Unlike Philip, he was afraid of the noise and the heavy pumping rods that were very close to the ladders.

Mary Davis was a ‘pretty little girl’ of 6 years old. The Government Inspector found her fast asleep against a large stone underground in the Plymouth Mines at Merthyr. When she woke up, she said:

‘I went to sleep because my lamp had gone out for want of oil. I was frightened, for someone had stolen my bread and cheese. I think it was the rats.’

Susan Reece, also 6 years of age and a door keeper in the same colliery, said:

‘I have been below six or eight months and I don’t like it much. I come here at six in the morning and leave at six at night. When my lamp goes out, or I am hungry, I run home. I haven’t been hurt yet.’

A coal mine was a dangerous place even for adults, so it’s no surprise that many children were badly injured underground. Here are some more quotes from children who worked in the mines at this time:

“Nearly a year ago there was an accident and most of us were burned. I was carried home by a man. It hurt very much because the skin was burnt off my face. I couldn’t work for six months.”

– Phillip Phillips, aged 10, Plymouth Mines, Merthyr.

“I got my head crushed a short time since by a piece of roof falling.”

– William Skidmore, aged 8, Buttery Hatch Colliery, Mynydd Islwyn.

“…got my legs crushed some time since, which threw me off work some weeks.”

– John Reece, aged 14, Hengoed Colliery.

Some children spent up to twelve hours on their own, underground, all alone in the dark. They had little time for school, and even when they could go to school, they were too tired to learn. They were often pale, undernourished and dressed in ragged clothing.

Shaftesbury wanted to do something about this terrible neglect. He had argued in Parliament for some time that new laws were needed to protect children. What was it that prompted Lord Shaftesbury to act on behalf of vulnerable people like this?

He had felt that God was prompting him “to devote whatever advantages he might have bestowed … in the cause of the weak, the helpless, both man and beast, and those who had none to help them.” The Bible teaches Christian believers to speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves – and it was this understanding of Jesus’ teachings that led him to take a strong stand against the mistreatment of children, and speak out on their behalf to protect and care for them.

Eventually, these three laws were passed:

- The 1841 Mines Act: No child under the age of 10 to work underground in a coal mine.

- The 1847 Ten Hour Act: No child to work more than 10 hours in a day.

- The 1874 Factory Act: No child under 10 to be employed in a factory.

In 1842, children under the age of 10 (and women) were no longer allowed to work underground. In 1860 the age limit for boy miners was raised to 12, and in 1900 it was raised to 13.

These were improvements at the time; but the continued use of child labour is considered unthinkable in today’s Western society.

In the world Jesus was born into, children, along with women, old men and slaves, were viewed as physically weak burdens on society who had little value in the community. In ancient Greece and Rome, many people even found it acceptable to abandon unwanted children along the roadsides and leave them to die.

But Jesus taught that children were not to be looked down upon, but to be loved and valued.

When Christianity became more active during the ancient Roman era (when Rome ruled most of the known world), the teachings of Jesus became more public and widespread. Jesus’ teachings about children were faithfully followed by the early church. The Christians taught that God cared for children, slaves and women, just as much as He did for men. Some Christians began collecting infants abandoned by their parents and raising them as their own. From the Christian point of view in this ancient time, both children and adults were equal in the kingdom of God.

It is this attitude to children that has driven faithful Christian believers like Lord Shaftesbury – and many others in history – to try to improve the lives of children in need.

These days, we have seen organisations like the United Nations start the Universal Children’s Day. Australia’s own Children’s Week Council of Australia holds the National Children’s Week each year in October to help draw attention to the needs of children and to value them. And while there are still many places in the world where children’s needs are sadly not met, it is great to be reminded of the work of caring and faithful people like Lord Shaftesbury who, prompted by his belief in the teachings of Jesus, fought to remind adults of their role in nurturing children and providing them with every opportunity to reach their full potential.

Written by Graham McDonald.